We don't need to run faster if we're running with the Spirit

The Red Queen dilemma and sharing the Gospel

Acts 11.1-18 and St John 13.31-35

Watch a pre-recorded version of this message on YouTube.

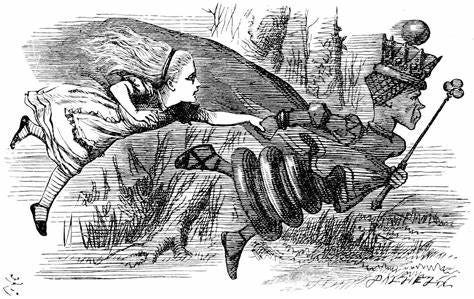

The Red Queen’s Race is an incident from Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass in which the Red Queen – who is merged with the Queen of Hearts in the Disney version of Alice in Wonderland – explains why one must run faster and faster to stay in the same place. As explained by Alice:

‘Well, in our country,’ said Alice, still panting a little, ‘you’d generally get to somewhere else—if you run very fast for a long time, as we have been doing.’

‘A slow sort of country!’ said the Queen. ‘Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least as twice as fast as that!’[1]

The example of ‘running in place just to stay the same’ has been used in multiple contexts, from evolutionary biology, to quantum physics to explain that nothing can ever reach the speed of light, to the resource demands of suburban sprawl, and to the struggles for Black liberation by Jay-Z.

Why it is so popular? Because it sounds so true. Have you ever felt as if you are running faster just to stay in place? And that to go anywhere requires an extreme amount of energy? That if you stop for rest, you go backward?

You are not alone. The disciples in the earliest days of the church felt the same. And if they did, then it is no surprise that we feel it today, too.

How do we get around it? The simple answer is: We follow the Spirit, which moves faster than our understanding, and pulls us beyond the limits of our imagining.

Living this out is harder, as the disciples of Jesus well knew. This time between Easter and Pentecost is an anxious time. We are supposed to celebrate: Christ is Risen! Christ is Risen indeed. Alleluia! But tugging at us like the inertial languidness of a hot summer day are the pregnant pauses of the disciples. The daunting task of ministry in front of them was too much: they did not see how they could expend any more energy than they already had! They knew that just to live they had to ‘run in place.’ When Christ was with them, all the ordinary stuff seemed so insignificant: having jobs, living in a house, making ends meet. But with the physical Jesus gone, the innovative ministry they once knew was too hard, too scary, to do without Jesus. They had seen what happened to Jesus, and they did not want that to happen to them. The price seemed so high. So, they did not rush out of their hiding place after receiving news of the resurrection, even after witnessing the resurrected Christ in their midst. They remained hidden. In John’s gospel they slipped back to the Sea of Tiberias and resumed their fishing careers. They returned to what they knew, what was safe, and what was comfortable. Jesus had to go find them, to encourage them on to the next step toward a maturing discipleship.

The modern church (that’s us) in this in-between time reads the flashbacks to the time before the crucifixion, such as this interaction between Jesus and Simon Peter on the night before Jesus died. It is a confusing time—even the timeline of Jesus’ statement is odd:

‘Now . . . has been . . . has been . . . has been . . . will . . . will . . . a little longer . . . will.’[2]

Without knowing the cost of discipleship, Peter tried to cut through Jesus’ assertion that he will suffer and die. Peter pledged his entire life to Jesus in order to keep the things the way they are. But Jesus knew Peter was not ready for what was coming. Jesus had just called his own disciples ‘little children’. It was meant as an endearing term, but the impact would be about the same as if I called you a bunch of ‘dear little children’, or vice-versa: we would feel chastened, as if told we were inadequate. Yet here it proved true. When Jesus was taken into custody by government and religious officials, Peter denied knowing him. His resolve crumbled into fear.

Why? Peter was not ready. He could only think in terms of

the Red Queen’s dilemma of running in the same place. But the Spirit moves us beyond our own pacing. Through the patient work of God’s grace, he would become ready.

Are any of us ready? Are we too afraid of the Red Queen? If

we allow God’s grace to guide us, with patience it will make us ready. But

it’s not easy.

To follow Jesus is a process of growth and development, of trust and wisdom. With his disciples Jesus knew this, and he knew that the first reaction of these beloved little children—wizened fishermen, women with calloused hands, and grown-ups all of them—would be to cower in fear. But he could point them in the way they should go.

To grow from little children into disciples, they would need to practice one thing: Love. ‘Just as I have loved you, you also should love one another,’ Jesus said. The key word in that sentence is not love, though; it is ‘as’. That ‘as’ Jesus loved is woven throughout the whole gospel![3] It is how Jesus gathered people together, sought out the lost and the weary, challenged authority figures, and broke bread in stranger’s houses with a vast assortment of guests. If we want to learn how to be disciples, we should interrogate this command to love with two questions:

1) How is Jesus loving?

2) How might this inspire our loving now, so that we can love, and be loved, as Jesus loves us?[4]

If we are asking ourselves these two questions, and acting on the responses we get, then perhaps we will grow into the unity with God that God desires for us. That seems simple enough, but remember: for those first disciples, it meant that Jesus’ loving actions led him to be crucified by the people in positions of power and authority. How Jesus loves is so countercultural, so revolutionary, so subversive, that to love in a Jesus way will make you have enemies. It could lead to death.

Are you prepared for that?

It is helpful to know that God does not expect us to ‘get it’ all at once. The pull of the world’s fear, that you can never really get ahead, is too strongly imprinted upon us for most of us to immediately get it. God has patience. Peter had to go from his sophomoric promise of ‘I’ll do anything for you, Jesus,’ through denial, through challenge, to a Pentecost speech, to this moment, on a rooftop in a Greek land, praying to God for guidance. His ministry was not working. There was a clear divide, a distinction, between his cultural identity and these Gentiles. They could not eat together. He was running hard, but losing ground.

Jesus brought people together around tables, but because of religious and cultural differences, Peter could not do that. God’s new message was made clear to him: unity across cultural difference was more important than his personal, individual practice. ‘What God has made clean you must not call profane.’ It would have been highly discomfiting for Peter to eat at a Gentile table. But by doing so, he was demonstrating that God was welcoming those Gentiles and people of other cultures. He worked through this discomfort for the sake of the gospel.

Had he only clung onto that which he knew, he would not have participated in this new thing God was doing. His life and his ministry would have been circumscribed. And he would have felt he was falling behind. But the Spirit kept finding him, interrupting him, challenging his assumptions, pushing him beyond what he thought he could do.

This is how Jesus loves. It’s not a sentimental, kitschy niceness. It is a challenge that pushes you beyond what you thought could do, beyond who you thought you could welcome and accept, beyond what you thought was possible, and helps you realise that with God, you are not stuck in running faster just to maintain your position.

This is the boldness and courage that our world needs right now. We are in a time of hyper-individualism and near-unrestrained consumerism. People are lonely. They are isolated. They are either running at capacity already and barely staying afloat, or perhaps have given up, drifting ever more into a sort of hopelessness. What we offer as a church is counter-cultural. We offer togetherness, a ‘we’ that celebrates the ‘I’, but still prioritises the ‘we’, that reminds a person that you do not run alone. Fifty, sixty years ago, we were not counter-cultural: the community around us was very much about being together. Today, that is very much less true in Britain. (The tides are changing, though: a people, especially younger ones, are getting to the bottom of their individualistic odysseys and finding that they need to be on this journey of life with people, and increasingly, with God. We are the ones the world is looking for.)

How do we do that? We are still in an individualistic age. We cannot expect people to come to us. We have to go out them. Peter gives us a good model. He did not build a church, stick out a worship sign, and hope that a catchy slogan would sling people in. He had to follow what Jesus had asked by the shores of the Sea of Tiberias: ‘feed my sheep.’ Those ‘sheep’ ate food of different varieties, and he had to learn to eat and serve that food. He had to go to where they were and learn about them. He had to be curious about them.

The West End has changed dramatically in the 90 years that there has been a West End Church. It has changed dramatically in the past twenty years, too. We could try to stick to what we know, we really could. But the Spirit does not let us. It will find us, and it will reveal to us a new way to go, and engage with people for the love of God. Will we do it?

As Howard Thurman, that 20th century Christian mystic whose writings I cannot get enough of lately, wrote:

The movement of the Spirit of God in the hearts of men and women often calls them to act against the spirit of their times or causes them to anticipate a spirit which is yet in the making. In a moment of dedication they are given wisdom and courage to dare a deed that challenges and to kindle a hope that inspires.

The ‘spirit of our times’ is pulling people apart. It is leaving them hopeless, isolated, poorer in money and spirituality, and our church feels that pain because we, too, live in these days. But in prayer to God, we are called to be bold: a boldness borne of the loving style of Jesus, a boldness worthy of a counter-cultural church that brings people together in a time when people are brought apart.

Remember those two questions:

3) How is Jesus loving?

4) How might this inspire our loving now, so that we can love, and be loved, as Jesus loves us?[5]

If we rely on our own understanding, we will always feel as if we are caught in the trap of the Red Queen. Our loving now might look like loving new things. It might look like doing the deep listening we keep talking about doing. We might be surprised at what the Spirit reveals about us in each other and our wider community. Our loving now might look like showing up at community quiz nights as ‘West End Church’. It might look like joining in the campaign to learn something about how Newcastle University is transforming the General Hospital site. It might look like serving lunch on the first Tuesdays of the month. It might look like a worship service that has songs in it we don’t know. It might look a lot like what we are already doing, too: showing up for one another in times of trial, with a casserole or a phone call, just to check in. It might be offering a garden party or a Christian Aid high tea. It might look a lot like this place does on a Sunday morning, arms open wide to welcome anyone, anyone, anyone in who comes, and journey with them to find a home.

We may start our journey of discipleship as little children, moved by fear and emotion, but also equally open to awe and wonder. But the Spirit does not leave us alone. It pulls us. We may stubbornly not want to listen. We may argue with it. But in the end, it will continue to call us. God never, ever, lets you go.

So what can you do? Love, and be loved, in ever-creative ways.

The Lord be with you.

Ford, David. The Gospel of John: A Theological Commentary. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2021.

[1] Carroll, Lewis, Through the Looking-Glass and what Alice found there, Ch 2

[2] Ford, The Gospel of John, 265.

[3] Ford, 266.

[4] Ford, 266.

[5] Ford, 266.

That dang ol’ spirit.