Watch a pre-recorded version of this message on YouTube.

The story of Martha and Mary with Jesus is one of those stories that raises the hackles of many good and dutiful Christians, particularly those who seem to do all the work to keep things going (you know who you are, and so does everyone else). The story is about attention: where and how we place our attention, and how important our attention is to God.

In CS Lewis’ classic story, The Screwtape Letters, a veteran demon gives his nephew, Wormwood, advice on how to be a demon. That story, too, is ultimately about attention, and how to keep a human being in young Wormwood’s care from paying attention to God, love, or anything that is meaningful or matters. I was reminded of this story last week in a recent edition of a podcast, The Ezra Klein Show. The titular host was interviewing Kyla Scanlon, an economic writer, about something they called ‘the attention economy.’ The show’s title was: ‘How the Attention Economy is Devouring Gen Z—and the Rest of Us.’ A few quick notes, in case those are weird words and phrases.

First, ‘attention economy.’ This is a phrase for how our attention is turned into money. This is via things such as the apps on smartphones, Facebook, Instagram, Tiktok, sensationalised news headlines, and whatever else is used to capture your attention away from anything else, usually on the internet.

Second, ‘Gen Z’—and I’m told it’s not ‘Gen Zed,’ in the British pronunciation of the ultimate letter in the alphabet—is that generation of people born between 1996 and 2010. They are characterised as ‘digital natives’ in that the internet has been a factor in their lives since the day of their birth, whereas past generations have adapted to the internet at various phases of their lives. Further, they have been shaped by climate anxiety, a shifting financial landscape, and Covid-19.[1]

The podcast was focused on how Gen-Z has been sent into this wilderness of the internet, social media, and artificial intelligence with the previous generations having little to no idea how it will impact an entire generation of human beings: how they work, interact with one another, and whether it is even healthy for human beings to exist so closely wired into such technology. That experiment is still ongoing.[2]

What the Gen Z economics writer, Kyla Scanlon, expressed worry about was how attention in this AI digital world was being hoovered up and away from other things. She talked about how her writing skills have been made less sharp by interaction with AI. She talked about how algorithms determined, with extreme precision, what things would catch her attention and found ways to place that into the ‘black mirror’ of her mobile phone. This is writ large for Gen Z and, apparently, everyone else. She likened this to CS Lewis’ The Screwtape Letters.[3] The demon’s job is to divert the attention of the human away from God:

It’s all about how you demonize this human. Wormwood has a human within his care. His whole thing is to bring him into hell and away from God.

And the way that you demonize someone — you’d think you’d want them to go kill somebody, right? That’s how you would think of it. But it’s really just keeping that person stagnant.

All of Screwtape’s letters to Wormwood are about keeping him from feeling anything. Keep him in one place, don’t let him fall in love or get passionate. Just keep him base line and bored. Don’t let him do his prayers. Let him forget all meaning and purpose within his life. That’s when he will come to us, the demons.

And toward the end, Screwtape gets mad at Wormwood, and they eat each other, essentially.[4]

I think Scanlon gets it about right, don’t you? Do you have trouble paying attention? Do you get distracted? Do you find it more and more difficult to get passionate about those things you care about? Does nihilism—meaninglessness—seep into the corners of your life, making any movement, any hope, any dreams, any aspirations, feel ‘heavy?’ It’s so difficult to stay focused! And it has gotten even more difficult in this modern age, when not only is 175 times more information bombarding you as it did in the 1980s, but unlike a print newspaper delivered to your doorstep, this information is tailor-made to catch your attention.[5]

Why are we allowing our attention to be diverted? Some of it is the sheer volume hurled at us. But we also permit it. Why? In part because it is comfortable, like being able to play a video game and feel some control over something when we fear we’re barely in control of our lives. But it is also because consuming the sort of information we like gives us a sense of power. We feel we understand the world, and our place in it. Comfortable and powerful. Yet that feeling is a fleeting illusion, and we know it. Knowledge is not power, despite the oft-repeated phrase.

The same emotion sits behind our desire to remain busy. Sure, ‘busyness’ does not sound comfortable, but it gives something of an illusion of being in control of a situation. I often get accused of being ‘so busy,’ as a ready-made excuse for why I have not followed up on a call. Sometimes it is true. I should not aspire to ‘be busy.’ But we seek having something to do such that we have a purpose, and therefore power and agency, over a situation. We want to be in control of our destiny; being busy seems a way to do this.

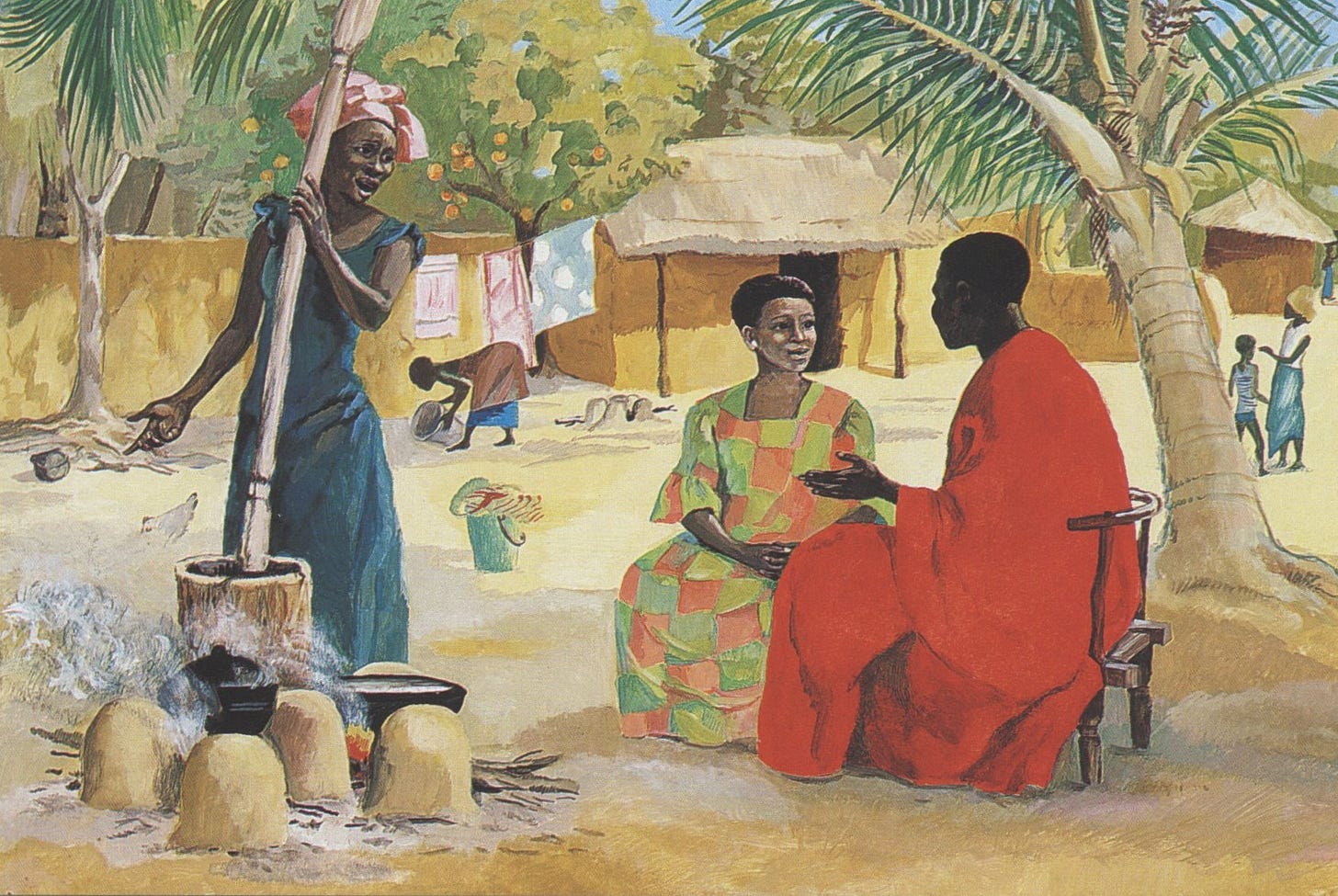

This brings us to Martha and Mary. One person sets about preparing for a meal, and is outside the room where Jesus, who had raised their brother from the dead, was sat. The other ceased doing anything and paid attention to Jesus. Martha’s famous tirade at Mary’s lack of assistance elicits Jesus’ response that ‘Mary has chosen the better part.’

Very often we find people riding to Martha’s defense: without Marthas, we have unclean dishes and no-one is ever served and treated with hospitality. But that is not what is in the Scripture. Mary is not declining from participating in the chores, ever. But at that moment, that first reconnection with the one who resurrected her brother, Lazarus (if we follow John’s timeline, John 11.1-40) and whose real divine power she has experienced, is in her presence. She stays with him, paying attention to him. The better part is to pay attention to the person in front of you. It is not a simple Martha and Mary binary, choosing one or the other. Rather, it is to ignore that which tries to ‘pop up’ on you for attention and pay attention to that which really matters. It is akin to paying attention to the needs of a child who needs a push on the swing rather than paying attention to the demands of the black mirror on your phone. It is recognise that a spouse needs your attention in a moment more than a work demand. It is to find a way to rebalance one’s life in such a way that paying attention to that which is really divine in our lives, such as love, rather than working ourselves silly to try and stay comfortable or keep things swimming along as they always have. To allow interruption for that which is truly divine is to allow oneself to feel, and be passionate, about the world. That’s what Jesus is inviting us into. It’s the opposite of busyness, distraction, the things that sap our attention, passion, and ability to dig deep and care about one another.

There is a real consequence to always being busy and distracted. Mary—and this Mary is not Mary Magdalene, but ‘Mary of Bethany’—chose to pay attention to their guest and to honour his presence with attention. After this moment, Mary would stay with him: she would feel his pain as he journeyed to Jerusalem. She would be there, with the other two Marys, at the foot of the cross, as he cried out his last words. She would feel the agony of his death in the core of her being, bearing witness to it as his lifeless body was pulled down from the cross.

Martha missed all of that. She provided the food, but she missed the journey and presence of Jesus. She is not recorded as being there. Her busyness was not focussed solely on the home and that moment when Jesus came. The story’s implication is that her busyness infected every aspect of her life, and kept her from the depths of attention, passion, and love.

Did she feel the pain that Mary felt, there on the foot of the cross? No, likely not. She did not put herself into the depth of that sort of vulnerable connection.

But Martha also missed the resurrection. For it was Mary, with Mary Magdalene, who went to the body of Jesus to tend to it, and discovered there was no body. Jesus was risen. She experienced it.

The hard question is placed in front of us: are we so busy, so occupied, so distracted, that we miss the resurrection? Are we too busy and distracted such that we fail to see love reborn in our midst? That is the risk: that we will miss seeing Jesus right in front of us.

So what do we do? We cannot give up. But it is not enough to say, ‘pay attention.’ The American Quaker theologian Parker J Palmer suggests that, ‘Learning is the thing for you.’ He recounts a story from the 1958 TH White novel, The Once and Future King, which recounts the story of Arthur and Merlyn. Merlyn has taken the young king under his wing, and realises that as the king ages, he will need to overcome sadness, despair, and meaninglessness, despite all the power and authority that comes with being a king.[6] A bored and passionless king is a dangerous thing. And so Merlyn teaches him to learn:

“The best thing for being sad,” replied Merlyn … “is to learn something. That is the only thing that never fails. You may grow old and trembling in your anatomies, you may lie awake at night listening to the disorder of your veins, you may miss your only love, you may see the world around you devastated by evil lunatics, or know your honour trampled in the sewers of baser minds. There is only one thing for it then—to learn. Learn why the world wags and what wags it. That is the only thing which the mind can never exhaust, never alienate, never be tortured by, never fear or distrust, and never dream of regretting. Learning is the thing for you.”[7]

I wonder how much of our busyness is really a bulwark against despair and fear of meaninglessness? How much of it is an attempt to convince ourselves that we matter? Child of God, you do matter. You are loved. Pay attention to the living God. Learn something each day that builds up your soul. Merlyn was not suggesting learning for the sake of a an accreditation, but learning for your soul: learning about beauty, love, and how to pay attention to this world. So pay attention to this gift of life that God has given to you. Do not let it pass you by. We never, ever, know when we might be hosting angels or the Lord of Heaven and Earth. We do not know what guises God takes; after all, something of God resides in each person you encounter. So do not occupy yourself with busyness for the sake of busyness. Pay attention. This is the better part. Thanks be to God.

Amen.

Works cited.

Klein, Ezra. ‘Opinion | How the Attention Economy Is Devouring Gen Z — and the Rest of Us’. Opinion. The New York Times, 8 July 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/08/opinion/ezra-klein-podcast-kyla-scanlon.html.

Palmer, Parker J. ‘Learning Is the Thing for You’. Substack newsletter. Living the Questions with Parker J. Palmer, 18 July 2025. https://parkerjpalmer.substack.com/p/learning-is-the-thing-for-you.

‘What Is Gen Z? | McKinsey’. Accessed 19 July 2025. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-explainers/what-is-gen-z.

[1] ‘What Is Gen Z? | McKinsey’.

[2] Klein, ‘Opinion | How the Attention Economy Is Devouring Gen Z — and the Rest of Us’.

[3] Klein, ‘Opinion | How the Attention Economy Is Devouring Gen Z — and the Rest of Us’.

[4] Klein, ‘Opinion | How the Attention Economy Is Devouring Gen Z — and the Rest of Us’.

[5] Klein, ‘Opinion | How the Attention Economy Is Devouring Gen Z — and the Rest of Us’.

[6] Palmer, ‘Learning Is the Thing for You’.

[7] TH White, in Palmer, ‘Learning Is the Thing for You’.